Explore the Chambers

Systemic Conflict Convergence

Central knowledge for conflict‑free justice

SCC is a public‑interest academy and legal archive. Our mission is to help courts, lawyers, and the public recognize and resolve institutional conflicts that threaten the rights of indigent defendants. We document doctrine, define terms, and publish practical guidance to preserve fairness at every critical stage.

This site will serve as a single, reliable place to learn: what “conflict‑free counsel” requires, how imputation works across institutions, and why neutrality of prosecution and tribunal matters to due process. We aim to turn scattered filings into accessible doctrine and a durable public record.

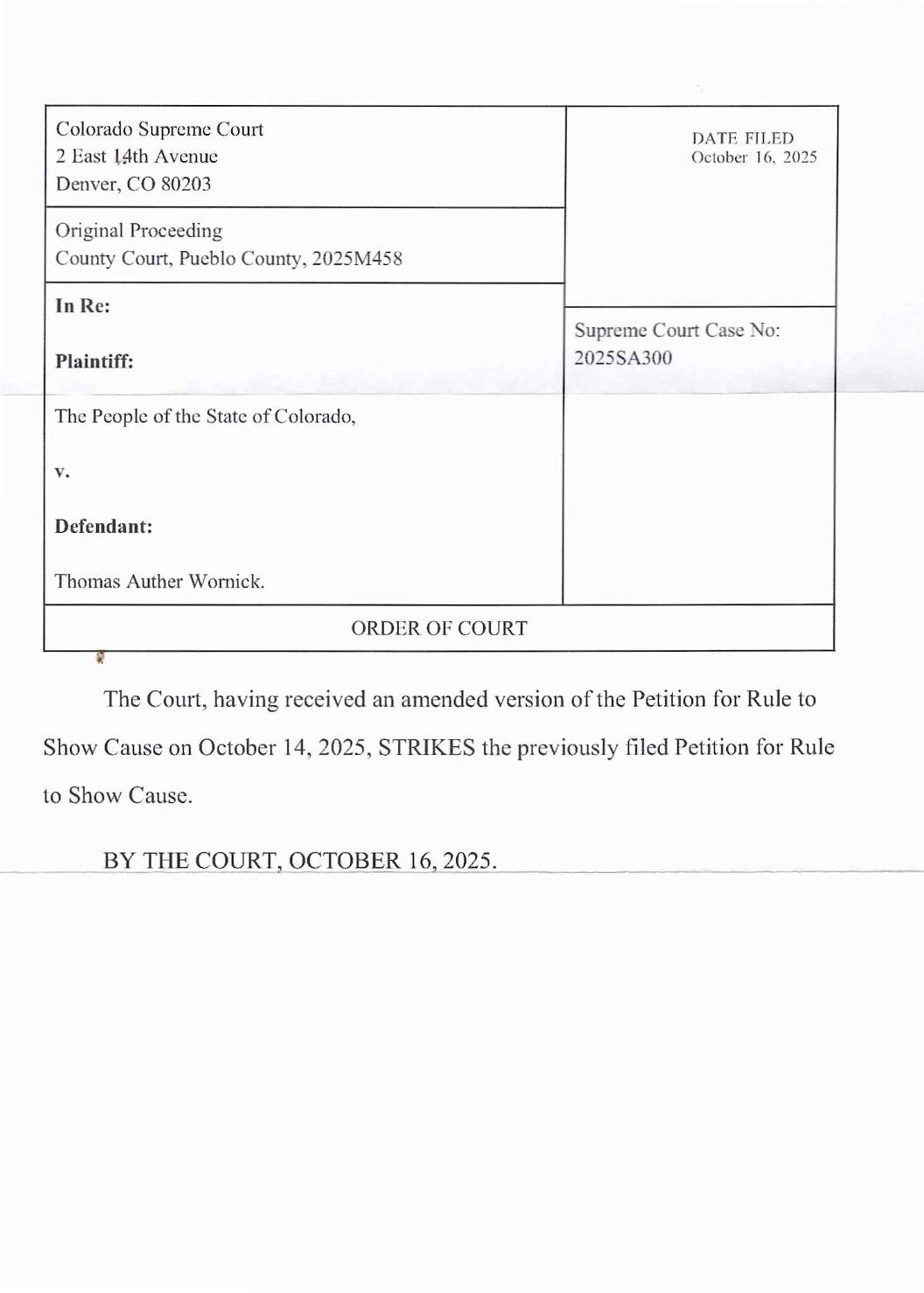

Colorado Supreme Court

2025SA300 Questions Presented:

1. Public Defender Conflict.

Whether the Sixth Amendment is violated when the Colorado State Public

Defender’s Office continues to represent a defendant while its statewide leadership

is simultaneously defending the Office against that same defendant’s conflict‑of‑

interest claims, creating an imputed, irreconcilable conflict under Colo. RPC 1.7

and 1.10.

2. Prosecutorial Conflict.

Whether due process is violated when the District Attorney’s Office, having

declined to investigate or prosecute a demonstrably false police report another

District Attorney’s Office used to secure an arrest warrant and over a year of

pretrial custody, turns around to charge the defendant with misdemeanor

obstruction of governmental operations based on petitioner’s alleged

communications demanding accountability for that same unaddressed misconduct,

thereby wielding the criminal process to punish a legitimate challenge to the

prosecution’s own unresolved conflict of Melissa Shopneck maliciously

prosecuting now‑dismissed charges while under conflict with a sitting judge her

office regularly does business in front of.

3. Judicial Conflict.

Whether due process is violated when the presiding judge conducts ex parte

communications with the District Attorney’s Office and prospective defense

counsel about the defendant’s mental competency before any counsel is formally

appointed and without an on‑the‑record conflict inquiry, even as parallel

proceedings in Denver District Court challenge unrecorded, weaponized

competency conflicts, thereby signaling prejudgment and denying the defendant an

impartial tribunal.

4. Systemic Conflict Convergence.

Whether the convergence of these structural conflicts, conflicted defense

counsel under the Sixth Amendment, conflicted prosecution under due process,

and a conflicted tribunal under Caperton, so eviscerates the adversarial process

and denies the defendant’s Sixth and Fourteenth Amendment rights that it creates

a systemic breakdown of the criminal justice system, presenting a question of first

impression requiring this Court’s original supervisory intervention.

5. Indigent Defendant Equal Protection and Due Process.

Whether indigent defendants are denied equal protection and due process

when structural conflicts infect the only counsel available, the Colorado State

Public Defender’s Office, while non‑indigent defendants can secure private,

conflict‑free representation “commensurate with that available to non‑indigent

defendants,” in violation of the Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments.

6. Veteran Leniency & ADA Accommodations.

Whether due process and equal protection are violated when courts and

prosecutors disregard a combat veteran’s military service, trauma, and

VA‑documented disabilities, and instead deny diversion or accommodations

required by federal law, contrary to the U.S. Supreme Court’s recognition that our

Nation has a long tradition of affording leniency to veterans (Porter v. McCollum,

558 U.S. 30, 43–44 (2009) (per curiam)) and the mandates of Title II of the

Americans with Disabilities Act, 42 U.S.C. §§ 12131–12134; 28 C.F.R.

§ 35.130(a).

7. Breach of Federal NPA and State Plea Agreement.

Whether due process is violated when a federal non‑prosecution agreement

conditioned on a state plea collapses because the State breaches the plea within

days of execution and provides no remedy for years, leaving the defendant without

the benefit of the bargain, in contravention of Santobello v. New York, 404 U.S.

257, 262–63 (1971), which held that when a plea rests in any significant degree on

a promise or agreement of the prosecutor, such promise must be fulfilled, and in

violation of the constitutional guarantee of fundamental fairness in plea bargaining.

8. Impossibility and Illusory Plea.

Whether due process is violated when the State induces a guilty plea by

promising diversionary programs or treatment courts that do not exist, rendering

the plea involuntary and illusory under the Fourteenth Amendment and the

Supreme Court’s plea‑bargaining jurisprudence, including Mabry v. Johnson,

467 U.S. 504, 507–11 (1984), holding that a guilty plea must be voluntary,

knowing, and not induced by unfulfilled promises, and Santobello v. New York,

404 U.S. 257, 262–63 (1971), recognizing that when a plea rests in any significant

degree on a promise or agreement of the prosecutor, such promise must be

fulfilled.

9. Conflict‑Free Counsel and Abandonment.

Whether the Sixth Amendment is violated when indigent defendants are

compelled to proceed with counsel who withdraws for private gain, conceals

conflicts of interest, or refuses to present the defendant’s chosen defense, thereby

depriving the accused of conflict‑free representation and constituting structural

error under Holloway v. Arkansas, 435 U.S. 475, 481–91 (1978), holding that

forcing joint representation over timely objection requires automatic reversal

because prejudice is presumed; Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668, 687–96

(1984), establishing that ineffective assistance requires deficient performance and

resulting prejudice undermining confidence in the outcome; and People v.

Bergerud, 223 P.3d 686, 693–96 (Colo. 2010), recognizing that forcing a defendant

to choose between counsel and the presentation of his chosen defense violates the

right to counsel and fundamental trial rights.

10. Judicial Bias and Competency Weaponization.

Whether due process is violated when the presiding judge, before appointing

counsel, engages in ex parte communications with the very public defender’s

office the defendant has identified as conflicted, and in those communications

suggests a competency evaluation, thereby prejudicing prospective counsel and

weaponizing competency proceedings to delay, silence, and suppress defense, in

violation of Caperton v. A.T. Massey Coal Co., 556 U.S. 868, 876–87 (2009),

holding that due process requires recusal where, under a realistic appraisal of

psychological tendencies and human weakness, the probability of actual bias is too

high to be constitutionally tolerable; and Pate v. Robinson, 383 U.S. 375,

378–86 (1966), holding that the conviction of a legally incompetent defendant

violates due process and that courts must sua sponte conduct a competency

hearing when evidence raises a bona fide doubt.

11. Brady Violations and Weaponized False Reports.

Whether due process is violated when the prosecution suppresses

exculpatory evidence and relies on demonstrably false police reports and dismissed

allegations to justify arrest, bond revocation, and competency proceedings,

contrary to Brady v. Maryland, 373 U.S. 83, 86–88 (1963), holding that

suppression by the prosecution of evidence favorable to an accused violates due

process where the evidence is material either to guilt or punishment; and

Thompson v. Clark, 596 U.S. ___, ___, 142 S. Ct. 1332, 1335–36 (2022),

holding that a criminal case terminates favorably for the accused when it ends

without a conviction, underscoring the constitutional bar against weaponizing

baseless charges once dismissed.

12. First Amendment Retaliation and Chilling Effect.

Whether the First Amendment permits criminalizing a citizen’s speech, even

harsh or extreme speech, including alleged “true threats,” when that speech

criticizes judicial and prosecutorial misconduct and arises as the only available

means of resisting a Systemic Conflict Convergence; and whether charges and

competency proceedings imposed in retaliation for such speech violate the

recklessness standard required by Counterman v. Colorado, 600 U.S. 66,

72–73 (2023), holding that the First Amendment requires proof that the speaker

had some subjective understanding of the threatening nature of the statement,

with recklessness as the minimum standard, and the constitutional guarantees of

free expression under the First and Fourteenth Amendments.

13. Cumulative Structural Breakdown.

Whether the convergence of a breached federal non‑prosecution agreement, a

breached state plea, conflicted defense counsel, conflicted prosecution, and a

conflicted tribunal constitutes a systemic breakdown of the adversarial process,

creating structural error that is not susceptible to harmless‑error review and

requiring this Court’s supervisory intervention to preserve the integrity of criminal

justice, in light of Arizona v. Fulminante, 499 U.S. 279, 309–10 (1991),

distinguishing between trial errors subject to harmless‑error review and structural

defects affecting the framework within which the trial proceeds; United States v.

Gonzalez‑Lopez, 548 U.S. 140, 148–50 (2006), holding that denial of the right to

counsel of choice is structural error not subject to harmless‑error analysis; and

Weaver v. Massachusetts, 582 U.S. 286, 294–95 (2017), reaffirming that certain

errors are structural because they undermine the fairness of the entire proceeding.

14. Speedy Trial Violation.

Whether petitioner’s statutory and constitutional right to a speedy trial was violated

when the prosecution and court failed to bring him to trial within the 90‑day

deadline mandated by C.R.S. § 18‑1‑405 and the Sixth Amendment, and when

conflicted counsel failed to preserve the violation, compounding the deprivation of

liberty and foreclosing meaningful review, in contravention of People v. Taylor,

2020 COA 79, ¶¶ 25–34, holding that dismissal is required when the government

fails to meet statutory speedy trial deadlines; People v. DeGreat, 2020 CO 25,

¶¶ 1–4, 461 P.3d 11, 13–14 (Colo. 2020), holding that the duty to comply with

Colorado’s speedy trial statute rests with the prosecution and the court, not the

defendant; and Huang v. County Court, 98 P.3d 924, 927 (Colo. App. 2004),

holding that “the speedy trial period is calculated separately for each criminal

complaint” and that dismissed charges are a nullity, with a new speedy trial period

beginning upon refiling, even if the charges are identical, citing People v. Allen,

885 P.2d 207 (Colo. 1994), and Meehan v. County Court, 762 P.2d 725 (Colo.

App. 1988).

15. Denial of Access to Courts.

Whether the First and Fourteenth Amendments are violated when an

indigent, pro se defendant is denied the basic tools of defense, subpoenas,

investigative assistance, phone calls, and uncensored legal mail, so that he cannot

prepare or present his case, thereby extinguishing the constitutional right of access

to the courts, in contravention of Bounds v. Smith, 430 U.S. 817, 821–25 (1977),

holding that the fundamental constitutional right of access to the courts requires

states to provide prisoners with adequate law libraries or legal assistance; and

Lewis v. Casey, 518 U.S. 343, 351–53 (1996), clarifying that denial of access to

legal resources or assistance violates the Constitution when it frustrates a

prisoner’s ability to bring a non‑frivolous legal claim.

16. Cruel and Unusual Pretrial Detention.

Whether the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments are violated when a

disabled combat veteran is subjected to prolonged pretrial detention under

retaliatory and restrictive conditions, including isolation, denial of

accommodations, and weaponized competency proceedings, thereby imposing

impermissible punishment before conviction, contrary to Bell v. Wolfish,

441 U.S. 520, 535–39 (1979), holding that under the Due Process Clause, a

pretrial detainee may not be punished prior to an adjudication of guilt, and that

conditions or restrictions that are not reasonably related to a legitimate

governmental objective constitute impermissible punishment; and

Kingsley v. Hendrickson, 576 U.S. 389, 396–97 (2015), holding that pretrial

detainees’ constitutional protections under the Fourteenth Amendment are

violated when officials impose conditions or use force that is objectively

unreasonable, regardless of subjective intent.

17. Double Jeopardy, Collateral Estoppel, and Interdependent Plea Collapse.

Whether due process, double‑jeopardy, and collateral‑estoppel principles are

violated when state prosecutors sequence a misdemeanor charge to extend time for

a federal indictment, dismiss that charge once federal prosecution commences,

then enter a federal non‑prosecution agreement conditioned on a state plea the

State knows it cannot perform, and, after breaching that plea and concealing the

breach for years, revive restraints and consequences despite the federal resolution,

thereby weaponizing dual sovereignty and plea interdependence to circumvent

constitutional protections, in contravention of Ashe v. Swenson, 397 U.S. 436,

443–46 (1970), holding that collateral estoppel is embodied in the Double

Jeopardy Clause and bars relitigation of an issue necessarily decided in the

defendant’s favor; Bravo‑Fernandez v. United States, 580 U.S. 5, 12–14 (2016),

reaffirming that acquittals have preclusive effect even when accompanied by

inconsistent verdicts; and Santobello v. New York, 404 U.S. 257, 262–63 (1971),

holding that when a plea rests in any significant degree on a promise of the

prosecutor, such promise must be fulfilled.

18. Forced Medication / Inadequate Mental Health Care.

Whether the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments, together with Title II of

the ADA and the Rehabilitation Act, are violated when state custodial staff

administer harmful and contraindicated medications, simultaneously withhold

effective, court‑authorized treatment, and layer multiple inappropriate drugs at

once, while erasing documented disability accommodations, creating an escalating

cycle of retaliation and neglect in response to grievances and abuse complaints;

and whether such practices, carried out amid acknowledged facility staffing crises

and withdrawn but coercive involuntary‑medication petitions, impose

unconstitutional punishment and deny minimally adequate care and liberty,

contrary to Estelle v. Gamble, 429 U.S. 97, 103–04 (1976), holding that deliberate

indifference to serious medical needs constitutes cruel and unusual punishment

under the Eighth Amendment; Farmer v. Brennan, 511 U.S. 825, 834–37 (1994),

clarifying that officials act with deliberate indifference when they know of and

disregard an excessive risk to inmate health or safety; and Washington v. Harper,

494 U.S. 210, 221–22 (1990), holding that the Due Process Clause limits the

State’s ability to administer antipsychotic drugs against a prisoner’s will, requiring

procedural protections and medical justification.

19. HIPAA / Privacy Breaches.

Whether constitutional privacy, due process, and equal protection are

violated when a defendant is court‑ordered into treatment and protected medical

and federal case information is unlawfully disclosed in violation of HIPAA; when

that breach is then used to accelerate a federal non‑prosecution agreement and

state plea; and when, after the State breaches the plea and conceals the breach for

years, the original HIPAA violation is weaponized against the defendant as

evidence of “conspiracy theories,” thereby silencing him while Systemic Conflict

Convergence suppresses a powder keg of public trust, contrary to Whalen v. Roe,

429 U.S. 589, 599–600 (1977), recognizing a constitutional interest in avoiding

disclosure of personal medical information; and NASA v. Nelson, 562 U.S. 134,

138–39 (2011), assuming the existence of a constitutional right to informational

privacy but relying on statutory safeguards such as HIPAA to protect it.

20. Custody‑Enabled Exploitation / Property Loss.

Whether the Constitution is violated when, during pretrial custody, a

defendant’s vehicle and financial assets are seized, transferred, and sold without

notice or hearing, contrary to Fuentes v. Shevin, 407 U.S. 67, 80–82 (1972),

requiring notice and opportunity to be heard before deprivation of property; and

United States v. James Daniel Good Real Property, 510 U.S. 43, 53–55 (1993),

holding that absent exigent circumstances, due process requires notice and hearing

before property seizure, losses that would have been avoided had conflict‑free

counsel safeguarded his rights, but instead went unchallenged because the Public

Defender’s Office, entangled in Systemic Conflict Convergence, prioritized

institutional self‑protection over the client, thereby violating the Sixth Amendment

right to conflict‑free representation recognized in Cuyler v. Sullivan, 446 U.S.

335, 348–50 (1980), and reducing not only property rights but the full spectrum of

constitutional guarantees, present and future, to collateral casualties of custody.

21. Forfeiture of Counsel Without Valid Waiver.

Whether the Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments are violated when a trial court

effectuates a forfeiture of the right to counsel by compelling a defendant to proceed

pro se without conducting a full, on‑the‑record Arguello/Faretta inquiry into the

defendant’s understanding, capacity, and voluntariness; and whether such a

forfeiture is constitutionally invalid where contemporaneous Systemic Conflict

Convergence exists, thereby rendering any purported waiver neither knowing,

voluntary, nor intelligent, contrary to Faretta v. California, 422 U.S. 806, 835

(1975), requiring a knowing and intelligent waiver of counsel; Iowa v. Tovar,

541 U.S. 77, 88–89 (2004), requiring trial courts to ensure defendants understand

the dangers of self‑representation; Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U.S. 458, 464–65

(1938), holding that waiver must be an intentional relinquishment of a known

right; and People v. Arguello, 772 P.2d 87, 93–94 (Colo. 1989), requiring a full

inquiry into capacity and voluntariness; and whether such a forfeiture constitutes

structural error not subject to harmless‑error review under United States v.

Gonzalez‑Lopez, 548 U.S. 140, 150 (2006).

22. Denial of Records and Evidence as Institutional Suppression.

Whether due process and the right of access to the courts are violated when

the court and prosecution fail or refuse to provide transcripts, discovery, and seized

defense evidence (including unsearched or unreturned digital evidence), thereby

preventing meaningful preparation, investigation, and presentation of the defense;

and whether such omissions, far from neutral error, operate as deliberate acts of

institutional self‑protection designed to shield and perpetuate Systemic Conflict

Convergence, contrary to Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12, 18–19 (1956), holding

that denial of transcripts to indigent defendants violates due process and equal

protection; Britt v. North Carolina, 404 U.S. 226, 227–28 (1971), requiring

transcripts when necessary for an effective defense; Brady v. Maryland, 373 U.S.

83, 87 (1963), holding that suppression of favorable evidence violates due process;

and Bounds v. Smith, 430 U.S. 817, 828 (1977), recognizing the fundamental

right of access to courts.

23. Judicial Vindictiveness in Response to Assertions of Systemic Conflict Convergence.

Whether due process is violated when judicial actions, such as initiating or

encouraging competency evaluations, restricting communication, or imposing

adverse case‑management rulings, are taken in direct response to a defendant’s

protected advocacy and explicit assertions of Systemic Conflict Convergence,

thereby creating the appearance of retaliatory motive, institutional self‑protection,

and compromising the constitutional guarantee of an impartial tribunal, contrary to

In re Murchison, 349 U.S. 133, 136 (1955), holding that a fair trial in a fair

tribunal is a basic requirement of due process; Caperton v. A.T. Massey Coal Co.,

556 U.S. 868, 872 (2009), holding that due process is violated where the probability

of bias is constitutionally intolerable; Tumey v. Ohio, 273 U.S. 510, 523 (1927),

holding that judicial interest in the outcome violates due process; and

North Carolina v. Pearce, 395 U.S. 711, 725 (1969), holding that judicial

vindictiveness in response to the exercise of rights violates due process.

24. Denial of Liberal Construction and Judicial Accountability.

Whether the First and Fourteenth Amendments are violated when the

Colorado Supreme Court, in 2025SA130, refuses to apply the settled rule that pro

se pleadings must be liberally construed, thereby extinguishing petitioner’s

constitutional claims on technical grounds and confirming that even the guardians

of justice have chosen silence over accountability, contrary to Haines v. Kerner,

404 U.S. 519, 520–21 (1972), holding that pro se pleadings are to be held to less

stringent standards than those drafted by lawyers; Boag v. MacDougall, 454 U.S.

364, 365 (1982) (per curiam), summarily reversing for failure to liberally construe

a pro se complaint; and Erickson v. Pardus, 551 U.S. 89, 94 (2007), reaffirming

that liberal construction is required to ensure access to courts and protection of

constitutional rights, as well as the broader principle of access to courts recognized

in Bounds v. Smith, 430 U.S. 817, 828 (1977).